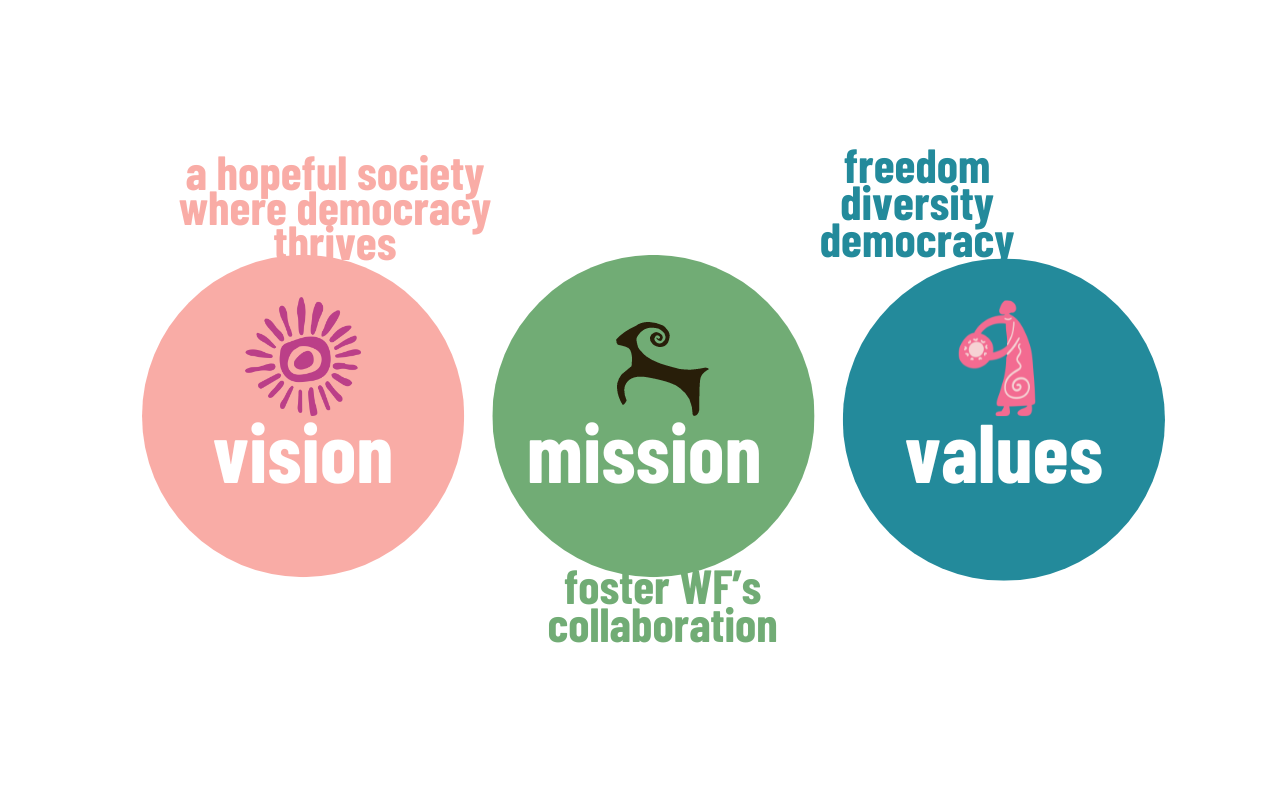

On the Right Track Initiative’s (OTRT) goal is to strengthen feminist, LGBTIQNB+, and human rights movements, ensuring that the values of freedom, democracy, and diversity are preserved and can flourish in the face of religious fundamentalisms and the far-right’s rising attacks.

We foster collaboration among women’s funds based on the deep conviction that the feminist movement is making democracy and human rights advance, leading the way toward a hopeful picture of a new society. Now, more than ever, supporting and amplifying this transformative work is essential.

Women’s Funds, Partnered Organizations, and Allies are participating to make OTRT possible. By joining forces, we can build a world where democracy and human rights survive and thrive.